Margaret Louise Laney

Margaret Louise Laney, niece of Augusta educator Lucy Craft Laney, was born in Washington, D.C. on May 25th, 1900. She was born to well-educated parents. Her mother, Anna E. Laney, was a practicing nurse and her father, Lucy Laney’s brother, Dr. Frank P. Laney, a doctor who graduated from the Howard University School of Medicine. After the death of her mother when she was still very young, her father made the decision to send her to Augusta to stay and be tutored by his sister. Louise, as she was called by most, attended school at the Haines Normal and Industrial Institute, the K-12 private institution established by Ms. Laney in 1883.

Growing up in the Laney household at 1116 Phillips Street was exciting but structured. Since Ms. Laney had no family of her own, Louise viewed her as much more than an aunt. There relationship was more along the line of a mother and daughter. In many ways Louise would pattern her life after Ms. Laney, from her attitude about education, the institutions of higher education she chose to attend, and her social and civic activity in the Augusta community.

Ms. Laney would allow students from Haines to board in her home, so there was never a shortage of children at their residence. Ms. Laney was a firm believer in discipline and structure. Everyday students staying under her roof had at least one hour of study time. In addition, there were certain dietary restrictions placed upon the children. No tea or coffee could be consumed in the Laney household.

Louise studied a variety of subjects at Haines. The options for students ranged from vocational to college preparatory training. Lucy Laney’s vision for Haines was to develop an institution that prepared the whole student, not just a specific discipline or skill set. She made sure that her students were exposed to a variety of subjects and that these subjects would in some way allow her pupils to tackle life’s challenges post-Haines. Louise Laney recalls some of the things expected of the students at Haines:

We learned to speak before the public. And we used to have what you call lyceum. And everybody had a chance to get up before the rest of them and speak. You either gave an address, or you recited a poem, or something like that. But everybody was given a chance to get up before the public so you could have poise and all, and it was called elocution.

Just as in the Laney household, Haines was efficient and structured, where students had a daily routine and educators were given the utmost respect. Louise recounts part of her daily routine:

But before we went to chapel we began the day by having Physical Education on the outside. Now, I look at these children not knowing how to walk. We marched. School was called for the day by a bugle. Boy they used to blow the bugle! Everytime we heard that bugle sound we knew it was time to take in school. The girls formed their lines by classes on the front, and the boys on the back. Now the girls could drill as well as the boys. We knew how to right face, left face, right about face, left about face, to the rear march, and all of that….there was a man who had been in the Spanish-American War, a Mr. Isaiah Blocker, and he had charge of the boys….We took our exercises out in the yard everyday, except when it rained. And we marched from the yard into chapel! Ladies first; and we marched in by twos and went into our row of seats; and then the boys marched in. Now, the thing about it was, we had music also. And nearly everybody could play an instrument of some sort. And our music teacher, who was a Fisk graduate, saw to it that his advanced students played for the marching for a week. But the boarding students had their weekly Prayer Meeting; they had their Sunday school, and they had church. Now, we had a regular chaplain for the school. And when we didn’t have one, we would get some minister from the city. One of the people who was always glad to come was a Mr. Silas Floyd, for whom that school is named.

After graduating from Haines in 1919, Louise followed in her aunt’s footsteps and attended and graduated from Atlanta University in Atlanta, Georgia in 1923. The Teacher’s College at Columbia University in New York became a pipeline for southern African-Americans wanting to earn advance degrees in education. Louise took advantage of this by earning a master’s degree in English on June 5th, 1929.

At the time that Louise was living in New York for graduate school the city was alive with activity. She would often entertain herself by going to shows, especially when Haines graduates were performing. She enjoyed movies and also going to see the Bolshoi dancers.

By this time her father had remarried, and it was the hope of her family in Washington that after graduate school she would return to D.C. permanently. But the “doctor’s baby” as she was affectionately called by her stepbrother, Frank, had other plans. Like many pupils of Lucy Craft Laney, Louise made her way back to Augusta and embarked upon what would be a very successful career as a principal, educator, and probation officer for the Richmond County Juvenile Court.

Following the death of Lucy Craft Laney in October of 1933, Louise succeeded her aunt as principal of Haines in 1934. She would hold this position for one academic year. Reverend A.C. Griggs took over for her in 1935.

Louise spent 18 years in the Richmond County Juvenile Court Justice System as a probation officer. The energy and dedication Louise exhibited in this career was a microcosm of the effort she put forth in her other professional and civic endeavors. She, like her aunt Lucy, dedicated her life to bettering the lives of young people in the Augusta community.

The next thirty years of her life would be spent in the classroom. Louise taught at three different schools during her tenure in the Richmond County School System: Peter H. Craig School, T.W. Josey High School and A.R. Johnson Junior High.

Louise thought about going back to her alma mater, Haines, to teach. However, the private institution born out of the mind of her pioneering aunt was going through financial difficulties. This caused Louise to look at other teaching opportunities. She accepted a position at Craig Elementary. This proved to be tricky at first because she was accustomed to working with older students. She would maintain her position at Craig until she accepted a position at Thomas Walter Josey High School.

Louise would eventually make her way closer to her home on Phillips Street, when she accepted a teaching position at Augustus Roberson Johnson Junior High School.

Like her aunt, Louise was a strict disciplinarian. Valerie Davis, a native of the Sand Hills community and student of Louise’s at A.R. Johnson, recalled how her mother was called to bring her a change of clothes when Ms. Laney perceived that her dress showed too much of her back.

Louise’s activity in the Augusta community was not relegated to just education. She maintained a very active civic and social life. On November 23rd, 1957, Margaret became one of the charter members of the Augusta Chapter of the Links, Inc.

One aspect of Margaret Louise Laney’s life post-1933 was protecting her famous aunt’s legacy. Louise was the living reminder of Lucy Craft Laney’s contributions to the Augusta area. Louise had blazed a trail in her own right as an educator and probation officer. However, Louise was never hesitant about reminding people of the impact Ms. Laney had on the educational and social fabric of the state of Georgia.

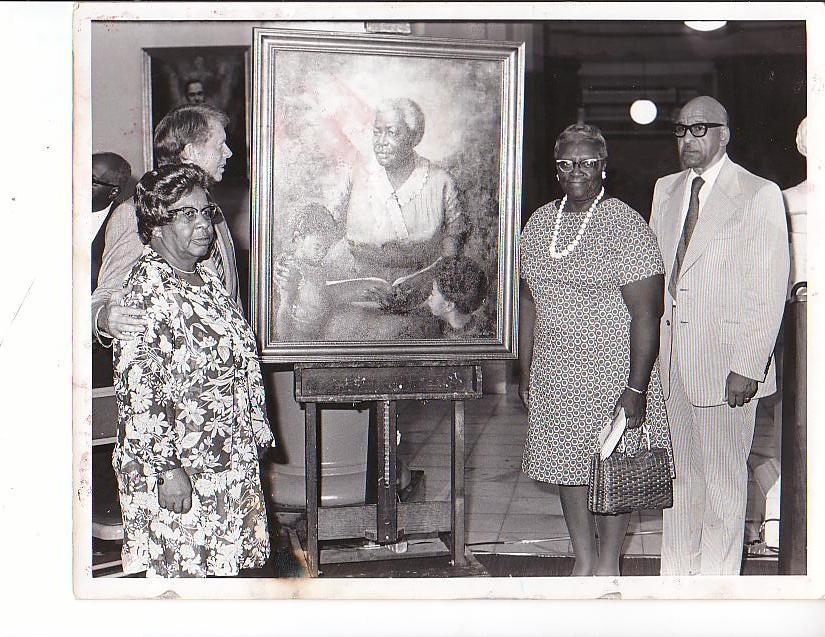

In 1974, Margaret Louise Laney, along with Georgia’s Governor Jimmy Carter, recognized the impact that Ms. Laney had on education for African-Americans, by unveiling a portrait of Ms. Laney to hang in the state capitol. Two years later, on May 31st, 1976, Louise Laney, with Dr. Benjamin E. Mays, former president of Morehouse College, Reverend Charles Spencer Hamilton, pastor of Tabernacle Baptist Church, local historian and activist Phillip Waring, educator and administrator Dr. Isaiah “Ike” Washington, and hundreds of others from Augusta and other parts of the state, renamed Gwinnett Street Laney-Walker Boulevard. The new name reflected who many historians consider two of the most iconic figures of the late 19th-early 20th Century: Reverend C.T. Walker, founder of Tabernacle Baptist Church and Lucy Craft Laney, founder of the Haines Normal and Industrial Institute and the Lamar School of Nursing.

Margaret Louise Laney died in 1986. The Laney Home caught fire, in which she was upstairs and unable to exit in time. Her funeral, held on the campus of Paine College at Gilbert-Lambath Chapel, was attended by hundreds. Her life was remembered by thousands.

In a letter to the editor on February 9th, 1977, Amy Thompson describes Louise as a “good neighbor” and someone with Rosa Tutt who “have been busy contributing to black history for many years in the areas of culture, education and racial understanding. Louise stood in the shadow of an American hero, her aunt, Lucy Laney, yet she carved out her own niche’ in Augusta, becoming a successful educator and servant of the public trust.